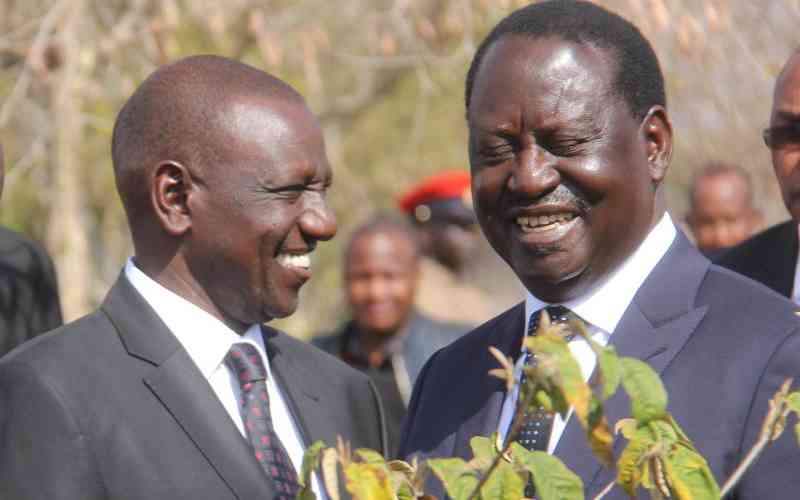

The formation of yet another government of national unity in order to quell national unrest has come as a surprise to many. Since the election results of 2022 were announced, the Azimio coalition has made known its displeasure, and organised against the Kenyan Kwanza government, claiming that the government was illegitimate.

It was therefore shocking for some to see members of the coalition happily joining forces with the government and accepting Cabinet positions. This is however not the first time that the opposition has been absorbed by the ruling power, and it speaks to a flaw in our democratic system.