×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

In July 2011, a new kid joined the block of 54 independent states of Africa. The autonomy of South Sudan was a welcome infant whose delivery signalled hope to her citizenry.

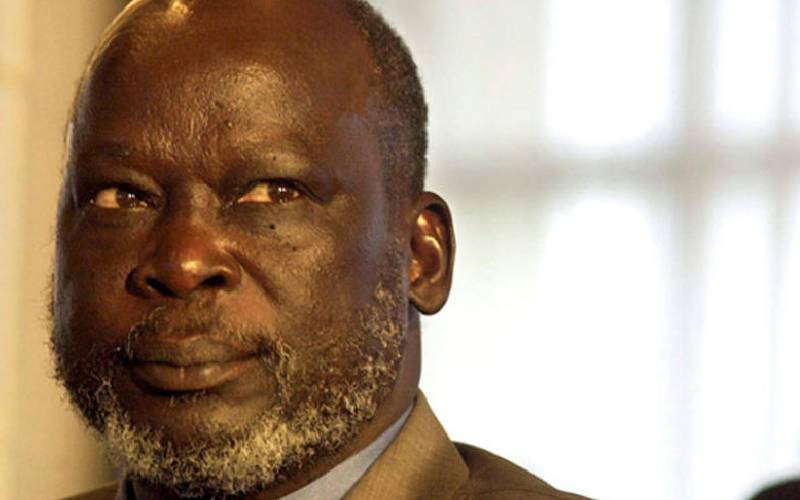

They earned the pride of sovereignty under the stewardship of John Garang along with his comrades in arms, under the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA).