×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

Many tears have been shed on account of the national identity card.

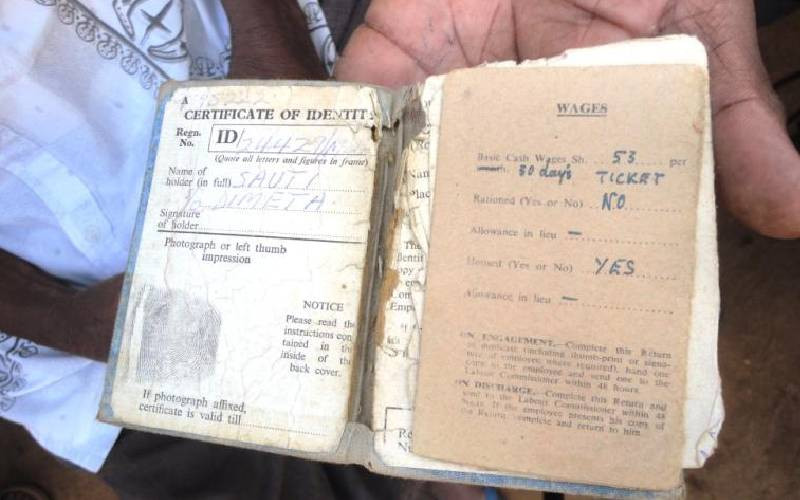

This document that carries one's identity in many forms, including a thumbprint, has been in use for more than a century. At the time of introduction, the document was meant to curtail the movement of Africans and was supposed to be displayed at all times.