×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

The recommendation of the Justice Aggrey Muchelule-led tribunal investigating the conduct of commissioner Irene Masit could see the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) without a team in January.

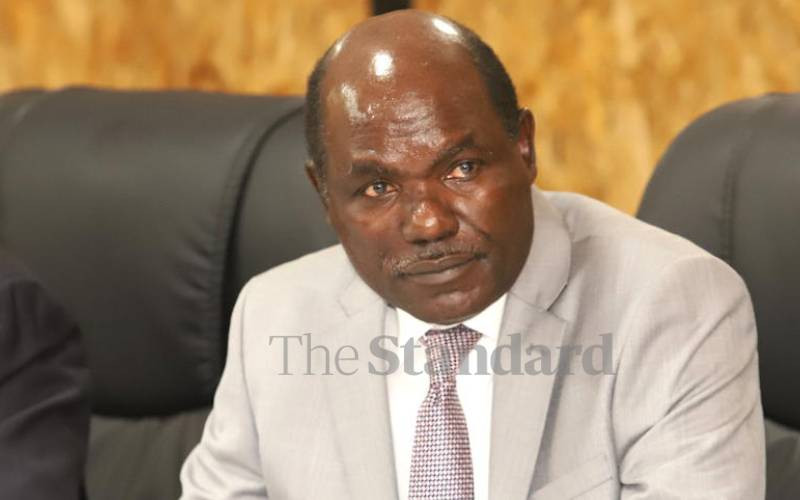

IEBC chairman Wafula Chebukati and commissioners Abdi Guliye and Boya Molu are set to exit this month when their terms in office end.