Imagine transporting trailer loads of currency notes along Kenyan roads. What a heist that would be for gangsters, who awhile back made cash-in-transit business a costly and dangerous affair? This has not always been the case for during Kenya's age of innocence, scenes of money being ferried in bulk were quite common.

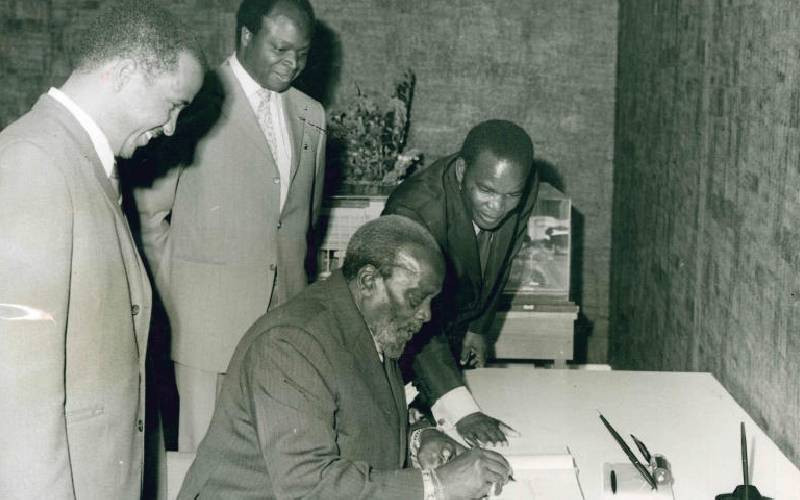

These scenes are best captured by Kenya's first Central Bank Governor Duncan Ndegwa who in his memoirs, Walking in Kenyatta Struggle: My Story, recounts how it was like in May 1967 when he took over from his predecessor.