×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

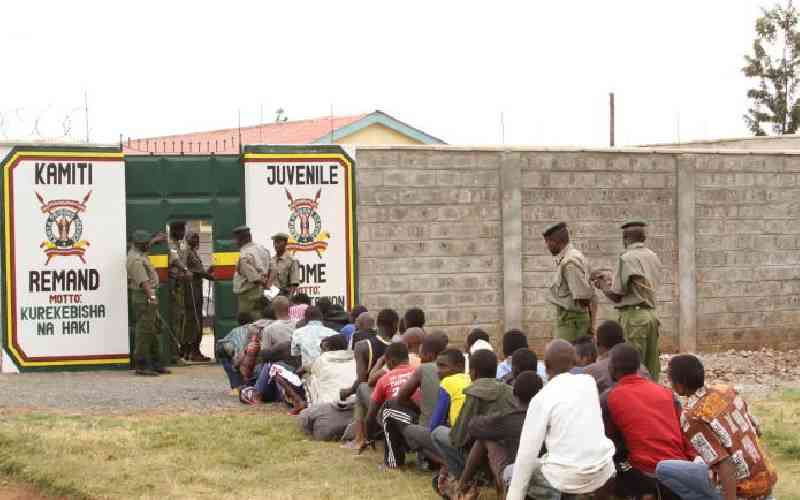

Minors in conflict with the law will now be corrected by the community and not hauled to courts and subsequently held in borstal institutions.

In a raft of sweeping changes introduced in the Children Act, 2021, children who end up in court for minor offences such as theft and arson will be corrected through diversion.