×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

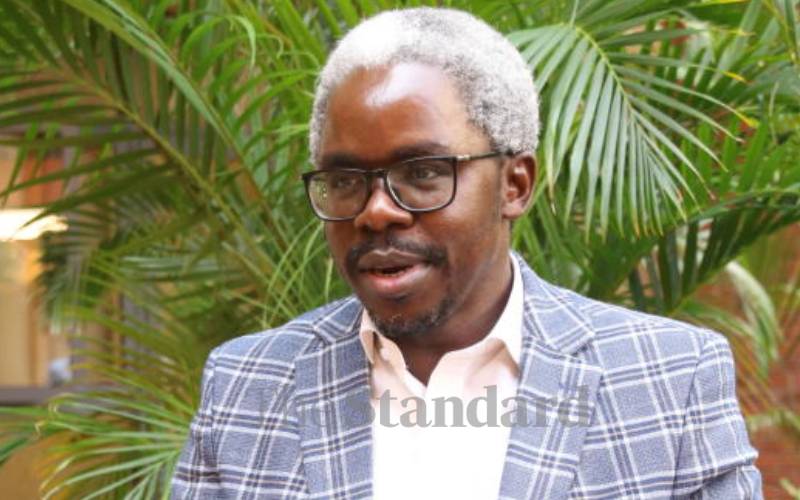

From when he was the size of his father’s boots, Prof Lukoye Atwoli knew he wanted to become a medical doctor.

About his fever and chills leading to admission and how the team of medics at the Kenyatta National Hospital fascinated his 11-year-old mind.