×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

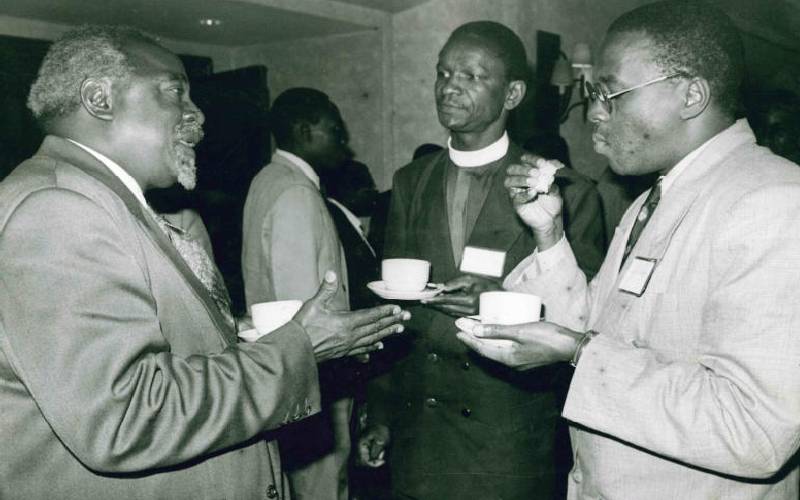

Nyakach MP Dennis Akumu (left) chats with Rev D Njoka (centre) and Willy Mutunga during a tea break at constitutional review conference held at Safari Park Hotel, Nairobi. [Standard, File]

The 5th anniversary of the passing of James Dennis Akumu was marked on August 18.