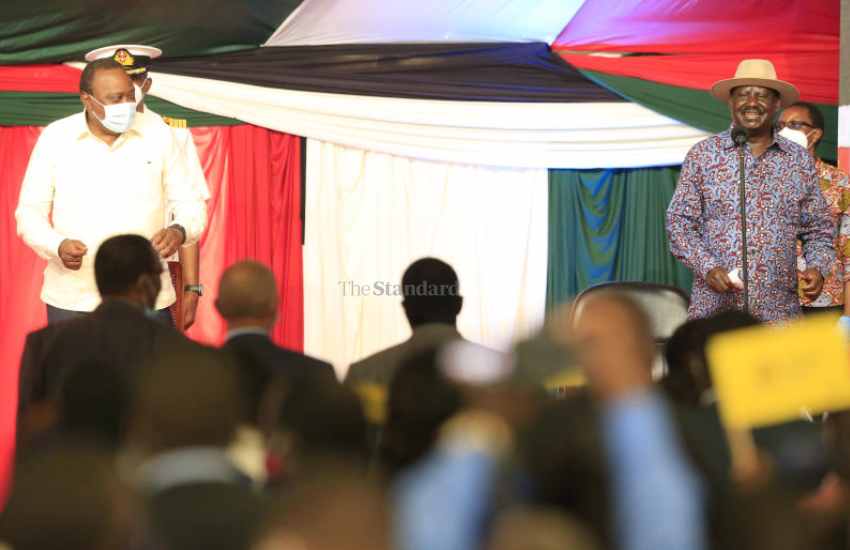

There appears to be developing political commotions in more ways than expected in the Mountain region and the Lake zone, both being on the Equator, in part because of growing uncertainty as to the future. Although the commotions are not new, they appear to grow in intensity, probably because perception exists of the existence of a leadership vacuum with the likely exit of two ‘brothers’, Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga, from the national political scene.

To compound the vacuum perception, a big Valley separates the Mountain in the east and the Lake in the west. With William Ruto, a hyperactive political ‘cousin’ to Uhuru and Raila, roaming the Valley freely, the perception of a vacuum is in the Mountain and the Lake, not in the Valley.