×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

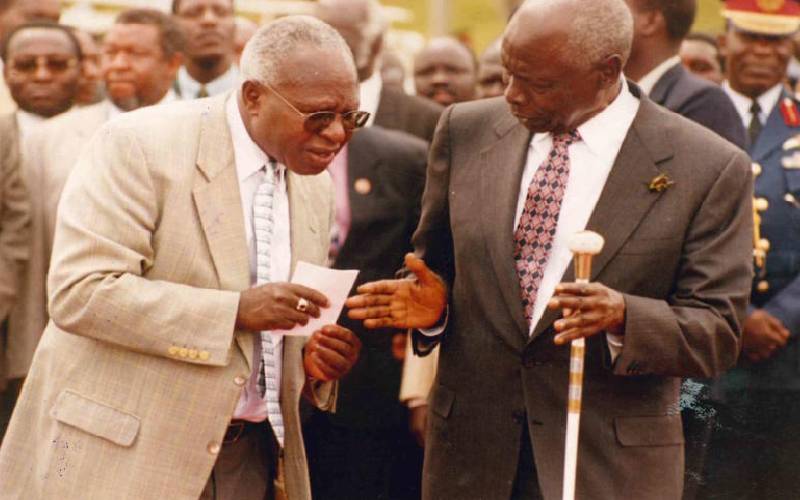

President Moi and Finance Minister Simeon Nyachae in deep conversation

Simeon Nyachae’s chequered life can be captured in three words -- power, privilege and influence. It was the power and influence of money on the one hand and the politics and privilege that goes with the two on the other.