×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

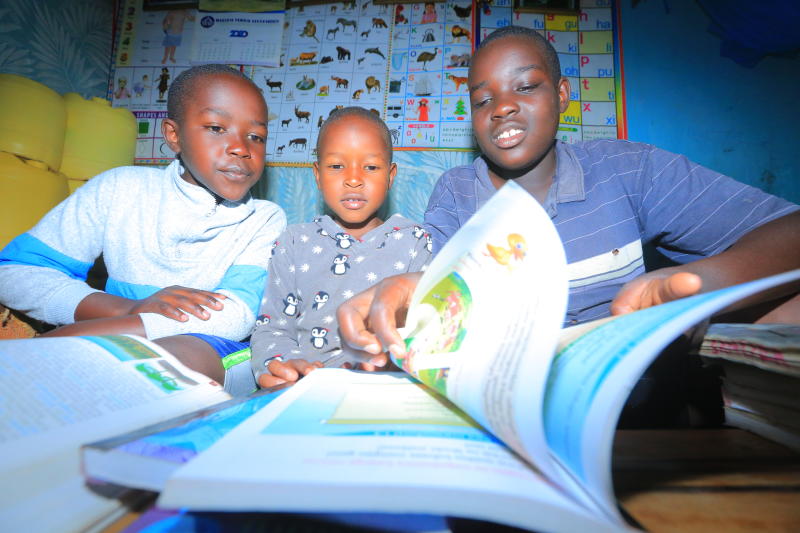

For weeks now, schools and local universities have been grappling with how to proceed with learning in the context of social distancing, curfews and mini lockdowns imposed as a result of the coronavirus.

Some universities have gone ahead to announce resumption of online studies as part of efforts to mitigate against what is termed as unforeseen interruption caused by the virus.