×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

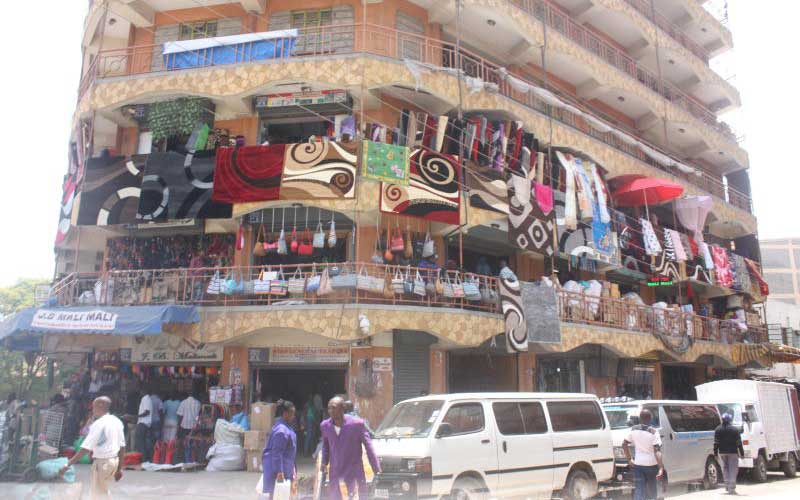

A section of Kamukunji market in Nairobi with assorted goods on display. [David Njaaga, Standard]

A gust of wind sweeps through the deserted corridors of a shopping complex in Nairobi’s Kamukunji market, the resultant howl eerie and lonely.