×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

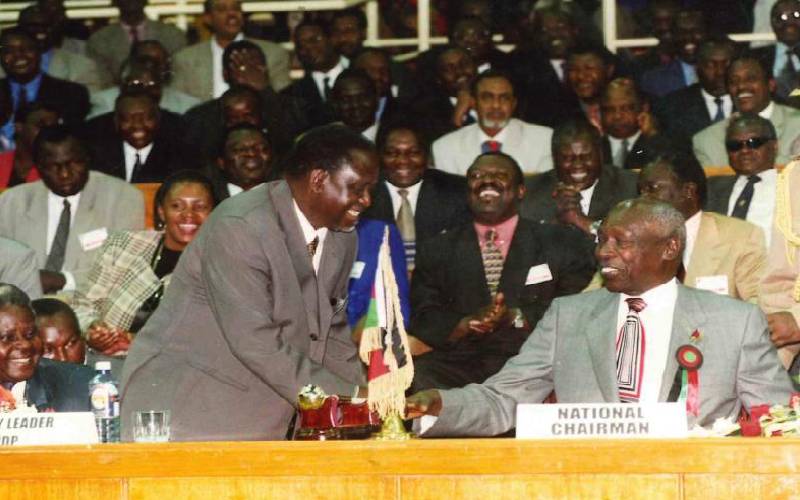

Former President Daniel arap Moi who will be buried today at his Kabarak home made the Kenya African National Union (Kanu) a behemoth that straddled Kenya’s politics for decades.

Moi, initially a member of Kanu, left the party to help found Kenya African Democratic Union (Kadu). He later rejoined Kanu.