×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

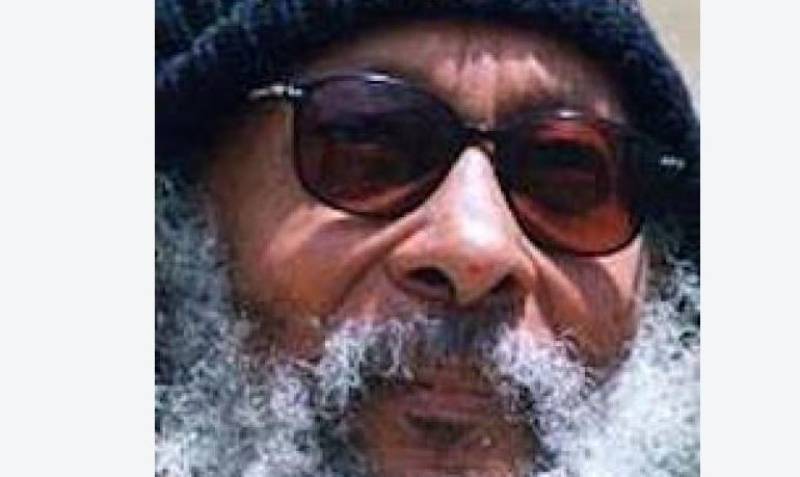

Sometimes in the 1980s, a Barbadian writer Edward Brathwaite (pictured) arrived in Kenya for the second time to visit his long-time friend and celebrated author Ngugi wa Thiong’o in Limuru.