×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

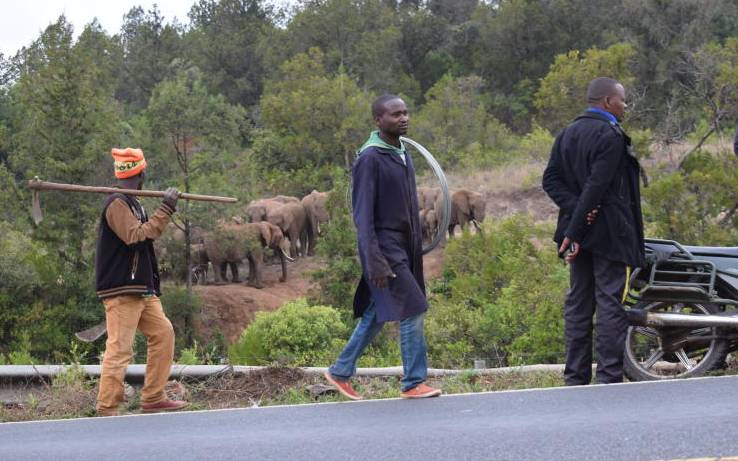

Road users stop to watch a heard of elephants crossing the elephant corridor along the Meru - Nanyuki highway on July 23, 2019. [Olivia Murithi, Standard]

Jane Kiptui is troubled. Her newly constructed fence and her maize farm have been trampled on by elephants in their annual migratory route from Laikipia through to Timboroa.