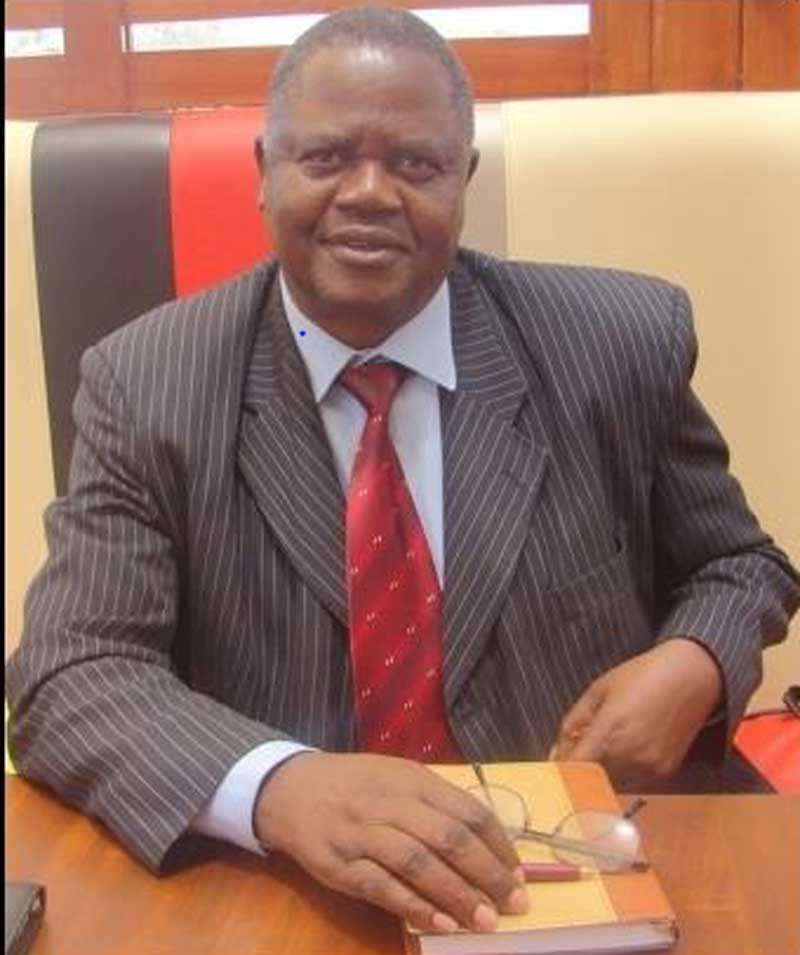

Chris Wanjala (pictured) was one of those people whom you encountered before meeting. His eloquent pen and incisive scholarly ethos went before him. I encountered him in the mid 1970s, when I was in high school and met him in 1979. The smiling youthful scholar lit up the pages of the Sunday Nation in the mid 1970s, with sprightly artistic writing that got you yearning to join the University of Nairobi. He gravitated across the landscape with scintillating perorations on negritude, African personhood and identity at home and in the Diaspora, verbal artistry, decolonisation of art and the language debate.