×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

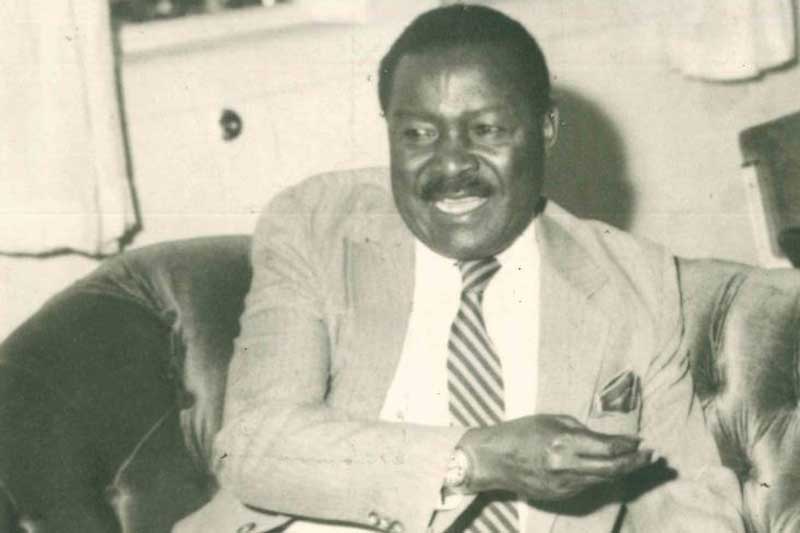

Former powerful Local Government minister Moses Budamba Mudavadi had more than Sh13 million in his bank accounts by the time he died on February 7, 1989.

The alumnus of Maseno and Alliance schools as well as Leeds and Harvard universities died at the Nairobi Hospital. He did not leave a written will, which put his Sh30 million estate at stake.