×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

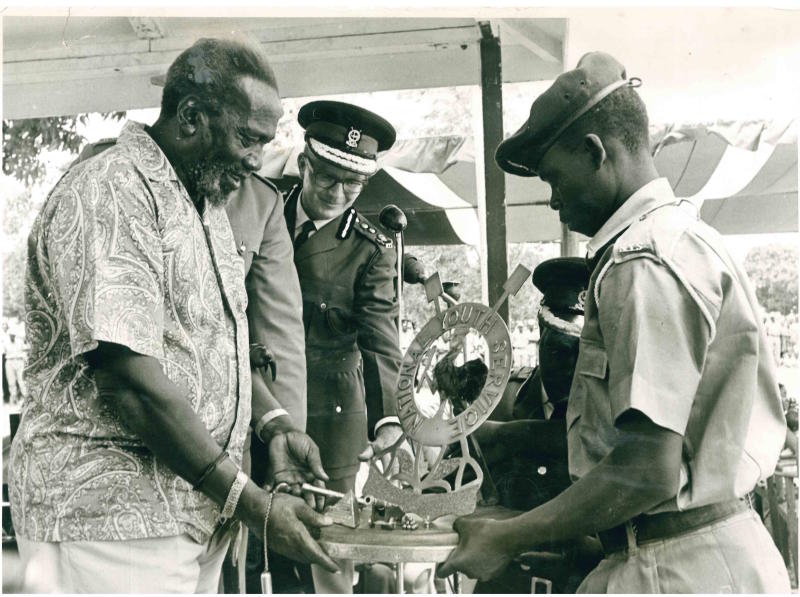

As inevitably as a moth helplessly gravitates towards light, the National Youth Service (NYS) has always attracted politicians and controversy from the day of its inception.

The paramilitary unit which has been transformed into a cash cow by well-connected entrepreneurs and conniving technocrats has always been irresistible to politicians.