It was school closing day and excitement among the boys was palpable. To ensure all was well, the school assistant captain who also doubled as the food prefect did his rounds and in one of the stores he found some paraffin. He emptied it into a tin and joined other students making their way out.

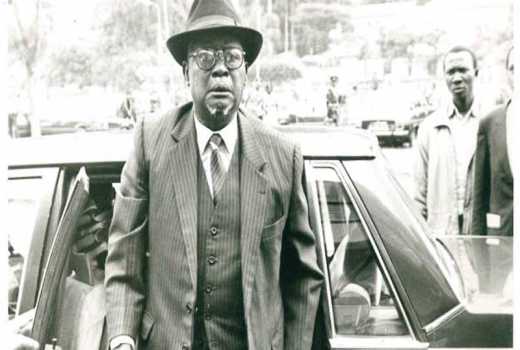

But as the prefect, Adonija Jaramogi Oginga Odinga happily marched out of school with plans of uninterrupted studies during the holiday now that he had oil to burn at midnight in pursuit of academic excellence, he was jolted back to reality.