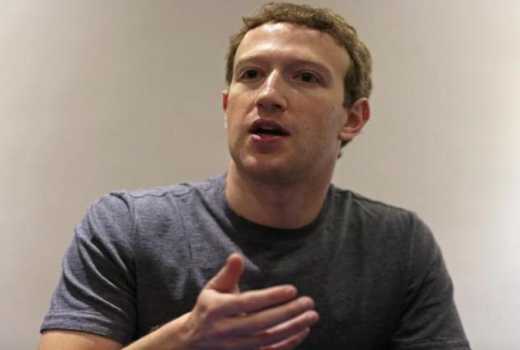

Mark Zuckerberg is under fire from Congress for failing to protect Facebook users’ personal information and for its inability to prevent Russia from using the social network to influence the 2016 presidential election.

While the site’s privacy troubles are recent, users have known about its other shortcomings for years. That Facebook can make us miserable is old news: so many research studies have concluded that it negatively affects our well-being, last year the company conducted its own such study and largely agreed. “I’ve been impressed by the consistency with which the scientific literature has uncovered negative links,” said Ethan Kross, director of the Emotion and Self-Control Laboratory at the University of Michigan, whose oft-cited 2013 research concluded that Facebook use predicts a decline in users’ well-being.