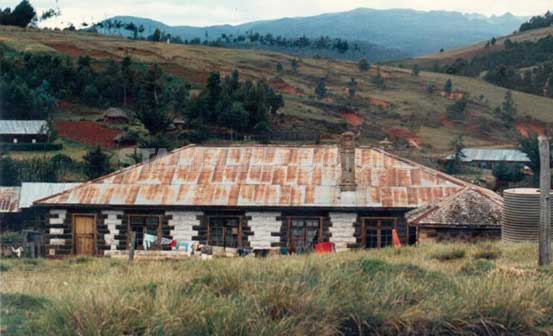

NAIROBI: A number of Kenyans responded to our story on colonial houses last week. Paul Too from Kericho wrote, “I would like to draw your attention to two interesting structures in Kericho County. The first is a colonial house that is in Kimasian High School near Londiani.”

“The house is in a bad state but its beauty is not lost. The second is Kipchimchim Catholic Church near Kericho Town. Apart from its unique architecture, it may be one of the few churches with frescoes. The paintings must be over 70 years old and they remind one of classical Italian art.”