×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

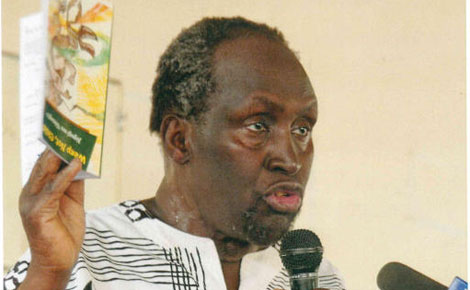

Ngugi wa Thiong’o, the father of Anglophone Kenyan literature, did not win the 2014 Nobel Prize for Literature, again. So what? It would be wonderful for a Kenyan writer and literature to be recognised through this prestigious award but the lack of it does not make Ngugi any less of a writer or indeed detract from his respected position as a literary icon.