×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

|

| Experts have warned over sharp increase in cases of mental illness |

By JOE KIARIE

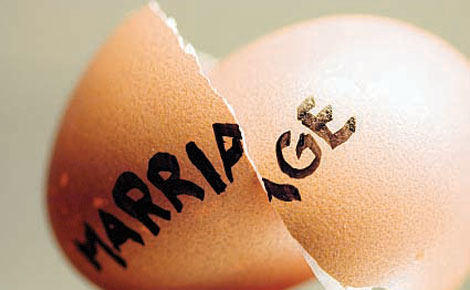

Kenya: Bloody terror attacks, insecurity, economic hardships and broken relationships have led to a sharp increase in cases of mental illness, experts have warned.