By Amos Kareithi

There was song and dance that harvest season as every farmer had ample millet. The fertile soils had not disappointed and neither had the spiritual leader who time and again had spearheaded a string of successful military expeditions.

That season, as the initiates faced the circumciser’s knife, the elders’ imbibed drinks happily, occasionally casting their heads heavenwards, thanking the gods for being so benevolent.

The toast of the community was their undisputed Orkoiyot, Kapchonge, variously known as Arap Oluoch, whose authority was undisputed among the people of Trans Nzoia, whom he had served diligently.

Like his fore fathers before him, Kapchonge was an Orkoiyot, a prophet, seer, military strategist and elder rolled into one. His office exuded power that engulfed both the high and mighty.

Entrenched in traditions

It is a mystery how the seer and his descendants who are believed to have originated from Somalia had continued to thrive so far away from their original home.

The institution of the Orkoiyot was deeply entrenched in the traditions of the Sabaot people from the days of Matui, who was famous among the Sebei (a sub- clan of the greater Sabaot), which his brother Psongoiywo called “The shots from the Pok side of Mt Elgon.”

His homestead was a preserve for a few and he was only accessed through appointments booked early in advance and the visitors cleared by his front office.

|

|

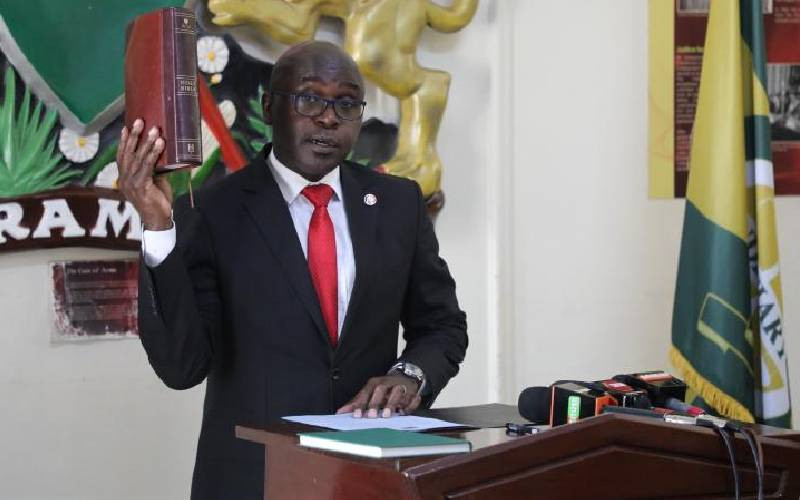

Silakwa recounts the history of the Orkoiyot. [Photo: Amos Kareithi/Standard] |

The seer had, however, become increasingly unhappy over a neighbour, Chepkoilel arap Cheruiyot who he suspected of belittling his powers although he was just an ordinary man.

The Orkoiyot or Laibon, as Kapchonge was known, decided to test his upstart neighbour by taking a calf and giving it liquor. He then summoned his neighbour and demanded to know why the animal was dazed and staggering.

After scrutinising the calf for a while, Cheruiyot said,” If this calf was a human being, I would say it was drunk; but since animals do not ordinarily partake of alcohol, I do not know what is wrong with it.”

The second and the ultimate test was conducted during the harvest. Two of the Orkoiyot’s daughters had been circumcised, an occasion that had presented the spiritual leader with immeasurable joy.

The Orkoiyot was, however, disturbed by the girls’ growing intimacy with Chepkoilel’s sons, and hatched a plan to nip the friendship before it was too late by declaring an abomination had been committed.

According to John Silakwa the secretary of the Sabaot Council of Elders (SCE), the Orkoiyot charged that the boys had breached traditions. The row between the Orkoiyot and Cheruiyot boiled over when the leader charged that his daughters had been violated and that the transgressors needed to be severely punished. He paraded all the newly circumcised boys.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

“During that time, the Oroikoiyot’s word was final; his verdict had no appeal. To avoid a catastrophe from the gods, Chepkoilel fled westwards but as he left, he cursed the ground of Trans Nzoia,” another elder, Michael Kitiyo added.

He declared that from then onwards, the soils of the place should not yield any harvest for the Sabaot people and further beseeched the gods that cows by his tribesmen in Trans Nzoia should never flourish.

Haunted place

To complete his string of curses, he pronounced that the sycamore tree that had sustained herdsmen in times of food scarcity should never flourish. This sealed the fate of the Sabaot in Trans Nzoia.

When the Orkoiyot heard that his rival had fled his birthplace and cursed it, he too feared that he might suffer from the wrath of gods for he knew he had unjustly accused Chepkoilel’s sons.

He also fled the area, but took the opposite direction, heading east, and left the Kitale plateau uninhabited for his followers too were afraid to continue to inhabit a land that had been cursed by their Orkoiyot and a layman.

The once fertile plains of Kitale became a haunted place where no Sabaot was willing to inhabit because of the fear of the age old curses although at one time, Kachonge’s descendants later trooped back after many decades.

They found that the Kapchaik branch of the community from Endebbes had also returned, and the two sides reached a compromise where the land was divided between them amicably.

“The Kapchaik were to occupy the land that was between 7,000 feet above sea level to 9,000 feet while Kamaratiek had to be content with the land below which included Kabras and Bungoma,” Silakwa explained.

Although the rivalry between Chepkoilel and the Orkoiyot has faded with time, the institution is still intact, though diminished in nature.

“We still have Orkoiyots and they are quite powerful and influential. There are two distinct branches of the institution, with the low and the highlands people having theirs different,” Silakwa adds.

He further explains, “The days of inter communal cattle raids and wars are long gone but we still respect our Orkoiyot.

Historical predictions

He has powers to summon elders. He has his own council of elders, who run errands for him.” Summons from the Orkoiyot are taken very seriously, the elders explain, and if the situation warrants, a common person wishing to have audience with the Orkoiyot must contact him through intermediaries.

“You cannot just go to the prophet and demand audience. He is not easily accessible. He has mystical magical powers and can thwart any such attempts,” Kitiyo says.

Although modernity has chipped off some of the Orkoiyot’s powers, he is still relevant and still retains some of his original powers, enabling him to predict famines, droughts and other natural calamities.

According to Sabaot Council of Elders, the institution of the Orkoiyot has made a string of historical predictions that have been proved right with the passage of time.

In 1860, the then reigning Orkoiyot, Mwisheyo, predicted the Bukusu would attack a fort in Ngalachi in Cheptais, which came to pass, leading to the famous battle of Kapukaya river where blood flowed like water.

Another seer, Matui, had predicted how the country would be dominated by men who came from the mouth of a long snake, which locals link to the coming of the white man aboard a train, a prediction that came true in early 1900.

Sangula, too, had prophesied that a very long and black snake would pass the area traversing from North East Kapenguria to Turbo, a prediction taken to mean the tarmac road that is now a permanent feature in the area.

The tumult that recently engulfed the Mt Elgon region after members of Sabaot Land Defence Force took up arms and waged a violent campaign had also been prophesied by an Orkoiyot.

According to Silakwa, the Orkoiyot had warned that there would be vicious fighting waged by youthful men that would engulf the entire Mt Elgon area.

During the fighting, residents intimated how the fighters had been inspired by their spiritual leaders, which granted them special powers that made them invisible to the enemy.

It took the intervention of the Kenya Army to root out the guerilla forces that had made the whole of Mt Elgon insecure and inhabitable. “Sangula, the current Orkoiyoit resides in the moorland of Mt Elgon, near Chepkitale. He is also known to reside in Labot and Chebyuk. You cannot reach him easily,” Kitiyo explains.

Bumper harvest

But even though there were talks of mystical powers of the present and past Orkoiyot’s, the elders are unanimous that their spiritual leaders are not witchdoctors.

Silakwa says: “An Orkoiyot is a powerful person with powers to predict the future. They do not poison or curse people to death. They were extremely important during times of war as they could foretell the outcome of a battle long before it was fought.”

Talking of cursing, the curses pronounced on Kitale and Trans Nzoia in general by the feuding Orkoiyot Kapchonge and his spiritually gifted neighbour, Chepkoilel have long been neutralised.

Immediately after independence in 1963, an elaborate cleansing ceremony, according to the Sabaot Council of Elders, was held where a white bull and sheep without blemish were sacrificed.

That is how the Sabaot agreed to return and own land in this area. “The soils once cursed now yield a bumper harvest and have transformed the area into Kenya’s maize granary,” Silakwa explains.

The numerous gigantic silos, scattered all over Kitale town are testimony that the area has outgrown the age-old curse purported to have been pronounced in 1600, further evidenced by the flourishing dairy sector in the area.

[email protected]

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.