×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

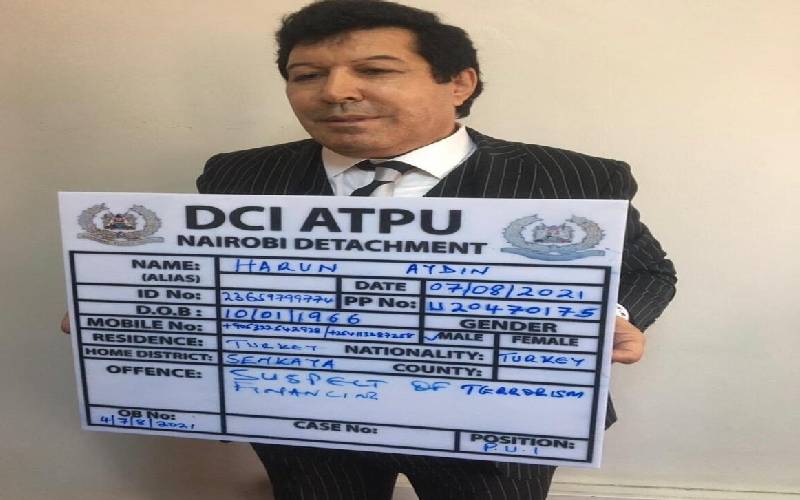

The Turkish national Harun Aydin when he was arrested.[DCI]

Few foreigners have caused as much of a stir as Harun Aydin, the Turkish national who left the country under unclear circumstances earlier this week.