Kenyan government ultimatum to close refugee camps by June 2022 will take centre stage at the United Nations deliberations in Geneva, Switzerland.

This comes as Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) new report released yesterday warns that pushing refugees to return to Somalia is not sustainable in current circumstances, with continuing violence, political instability and increasing displacement.

The report notes that closure of refugee camps would likely set stage for a new displacement crisis as it will completely force humanitarian agencies to withdraw from the region due to lack of funding and would result in total collapse of the camp economy, wiping out refugees’ only source of income and disrupting host communities’ livelihoods.

“The planned closure of the camps in June 2022 should be an opportunity to accelerate process of finding lasting solutions for refugees,” says Dana Krause, MSF’s country director in Kenya.

“At present, the mostly Somali refugees in Dadaab – many of whom have been trapped in the camps for three decades – face dwindling humanitarian assistance and limited options for leading safe and dignified lives,” says the report.

READ MORE

What UN, international community should pay attention to in DRC crisis

Let's manage water sustainably for future generations to enjoy it

Kalonzo, Wamalwa raise alarm over Haiti mission, warn of risks

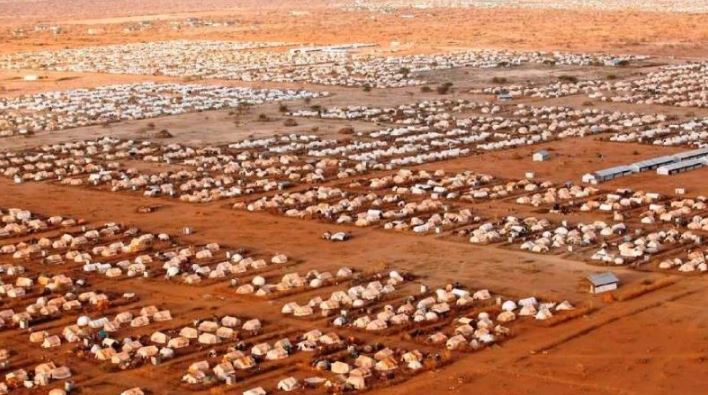

In June, Interior Cabinet Secretary Fred Matiang'i announced the closure of Kakuma and Dadaab camps by June next year. Nearly half of the refugees in Kenya (44 per cent) reside in Dadaab, 40 per cent in Kakuma, and 16 per cent in urban areas (mainly Nairobi), alongside 18,500 stateless people.

Dr Matiang'i said in a statement that he has provided UNHCR Commissioner Filippo Grandi with a timeline for the closure of the two refugee camps by June 30, 2022.

The process, planned to begin on May 5, 2022, will be expedited by a government team and UN refugee agency experts.

But UNHCR responded, saying that evicting the refugees from Dadaab and Kakuma camps, which have populations of 218,873 and 196,666 registered refugees, respectively, will be catastrophic.

The MSF report dubbed “In search of dignity: refugees in Kenya face a reckoning," calls on Kenya and its international partners to live up to the commitments made in the 2018 Global Compact on Refugees by allowing Somali refugees to integrate into Kenyan society or be resettled abroad.

“Even as rich countries have flouted refugee rights, Kenya has remained generous in hosting hundreds of thousands of refugees for years,” says Krause.

“As we mark the 70th anniversary of the Refugee Convention this year, Kenya should seize this opportunity to turn the tide and find lasting solutions which have the interests of refugees at their heart.”

The report notes that communities are increasingly dependent on aid, just as that aid evaporates.

“Undocumented refugees in the camps have little access to humanitarian assistance and are already struggling to survive. Closing the camps would put them at increased risk, especially if they are forgotten in the search for solutions,” reads the report.

“Many refugees in the camps have chronic medical conditions and will need continued access to quality medical care, especially those with conditions requiring lifelong treatment, such as HIV and other congenital diseases."

With the deadline to close Kenya’s refugee camps just months away, urgency is mounting to find sustainable solutions for the refugees in the camps at Dadaab, who risk being deprived of the little assistance they currently receive, warns

According to the report, the number of refugees returning voluntarily to Somalia has fallen sharply over the past three years, coinciding with rising violence, displacement and drought in the horn of Africa nation.

The move, MFS notes comes in the backdrop of resettlement offers from rich countries largely drying up, leaving refugees with little choice but to stay on in Kenya, where they have limited rights.

Refugees in Dadaab are currently barred from working, travelling or studying outside the camps.

In focus groups, refugees say in the report that all they want is integration into Kenya, with the second most popular option being resettlement into a third country.

The recent signing into law of Kenya’s Refugee Bill by President Uhuru Kenyatta could provide the chance for greater integration of refugees within Kenya, but this is dependent on it being implemented broadly to include all refugees, including Somalis.

“Kenya now has a simple choice: to let refugees slide further into precariousness, or to champion their rights by offering them the chance to study, work and move freely,” says Krause.

“Donor countries must share responsibility by increasing development assistance to Kenya so that it can ensure refugees have access to public services.”

The plan to close the camps has already caused humanitarian assistance to plummet, with the World Food Programme warning in September that it may be forced to stop distributing food rations altogether by the end of this year if more funding does not arrive.

Jeroen Matthys, MSF’s project coordinator in Dagahaley, one of the three camps that make up Dadaab says: “What we fear most is that closing the camps without offering solutions to refugees could result in a humanitarian disaster.”

“It is vital that refugees have uninterrupted access to humanitarian assistance throughout the camp closure process and until they have certainty about their future and can become self-reliant,” Matthys adds.

robala@standardmedia.co.ke