I'm no fan of Standard English. Indeed, I consider it a myth imposed, within Britain, by the elite upon a 'provincial' majority who are daily made to feel inferior because of their dialect differences; differences maligned as 'inferiorities'.

Within Britain, Standard English is a cultural weapon used by the ruling Oxbridge-London axis, an axis of class and geography. This is thankfully changing, slowly.

Perhaps ironically, I am myself Cambridge-born, Oxford-educated, and speak Standard English with a borderline 'received pronunciation' accent. But I don't respect the history of oppression that such a cluster of privilege is associated with.

Being a poet, I believe in empathy. Being a socialist in the broad sense of that term, I dislike the marginalisation and the linguistic and other privileges of 'elites'.

Consequently, I agree with Mukoma wa Ngugi, who last week celebrated African literature written in African languages. After all, I write in my mother tongue (English) and he, too, writes in the language that he seems most comfortable with (again, English).

When British Imperialism reached its violently criminal hand across Africa, it also licked its muscular tongue over our East.

English was cruelly and cynically imposed upon, especially, 'chiefs' sons' whom the British thought amenable to British cultural values. Any African aspiring to collaborate was expected to become cheerfully Anglophone.

Ngugi wa Thiong'o narrates the appalling injustice of schoolchildren being humiliated for speaking African languages in African schools.

There can never be any justification for alienating people from their mother tongue, any more than there can be any justification today for us giggling at those who 'shrub' English.

In our conservative infrapolitical acts of laughter from the schoolyard to the Churchill Show, the shame associated with 'mispronouncing English' is a post-colonial abuse that we daily commit against ourselves.

My personal (and Constitutional) view is that in 21st-century Kenya writers should pen literature in the language of their choosing, and that anyone denigrating mother tongue is deriding an important aspect of people's lives.

This belief led me, in an earlier article, to celebrate those of our talented young Kenyan writers who retain unglossed words and rhythms from other languages, for those moments of mother tongue insertion signify their culture and refuse to be overwhelmed by English.

Where the excellent Mukoma wa Ngugi and I differ, is over this issue of 'choice'. My position is that those who wish to write in mother tongue really should, and should be supported by the whole literary machinery of Kenya. Unfortunately, this isn't the case, and mother tongue publications often wither; this is not perhaps true of published 'vernacular' music, but is true of written literature.

This can change. Mukoma, on the other hand, seems to implicitly believe that Kenyan writers in place (he is himself a talented diasporan) have an obligation to write in mother tongue, whether they feel comfortable with this or not. I believe in choice and rights; he believes in 'muscular musts' and compulsion.

We agree, however, on the core issue of mother tongue being respected as a medium of communication and a carrier of culture.

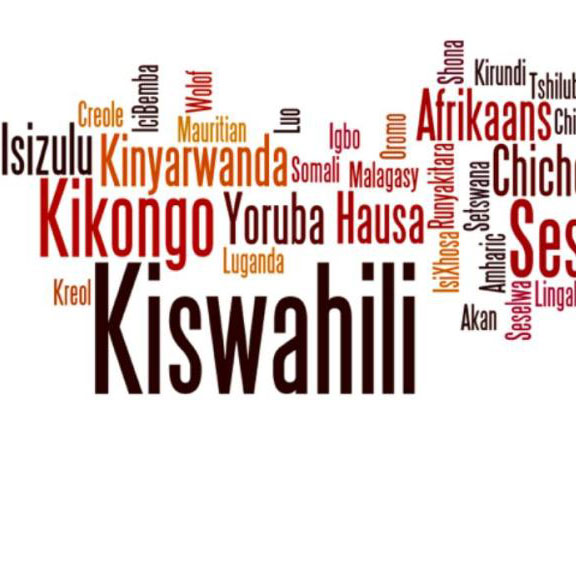

But why compulsion? I know many Kenyan writers who feel happy speaking their mother tongue, but who feel that their fiction only comes out 'right' when it's written in Kenyanised modifications of the two biggies, Kiswahili and English or, increasingly, Sheng of various forms.

Who are we to condemn them as traitors, especially since, as I hinted in that earlier article, they still pepper their works with meaningful uses of 'African languages', demonstrating that they're capable of making English bend to the weight of their 'African experience', as Achebe always believed possible?

Achebe was in part responding to the comments of Obiajunwa Wali, who stated at a famous 1963 Makerere Conference that only African languages can convey a truly 'African sensibility'.

While I believe that Wali was correct to some degree, and while I believe that he was making a strategically important political point at Independence, I think that his lack of theoretical rigour or evidence that languages (and the 'ethnic peoples' who speak them) are fully discrete means that his essentialist points have aged badly following decades of scholarship on linguistic and cultural hybridity, translation and rapprochement.

Ngugi Snr is essentially a 'Walian'. Indeed, I now agree with most scholars and practising postcolonial writers that the idea that languages are isolated like the criminal colonialists isolated 'the Kikuyu' into unforgiveable reserves, is wrongheaded and potentially dangerous, leading to the belief that peoples cannot fully interact beyond closed 'ethnic groups'.

Human experience is only restricted by language if we oblige ourselves to accept the myth of 'pure' mother tongues or a 'pure' Standard English.

While languages are never inherently ethnochauvinist, the manner in which we interpret and employ them really can be, and I think Kenya, like any country, is better off when people use languages in diverse and varied ways, mixing and sharing and stressing the manner in which we can exchange cultural understanding, accepting that our existing languages are already historically hybrid.

Ngugi Snr, for example, is no 'tribalist', and his most recent work evidences this. However, his use of Gikuyu is so often viewed by the unfairly critical as 'evidence' that he is 'tribalist'. It is important that we have writers who use Gikuyu, Dholuo, the (Ken) Indian languages, English (es), Kikamba, Sheng and so on. And it's important that they choose, rather than feeling obliged and intimidated by those who might play the 'I'm authentically "African"' card.

All languages are capable of being 'really African'. To state otherwise is to be, here, the post-colonial equivalent of those appalling British racists who insist that every immigrant must speak the Queen's English.

English cannot be exonerated from its vile past, but it can be appropriated by those of us in the post-colonies, as Kamau Braithwaite has proven with his Caribbean use of 'Nation Language', or as South African oral literature has proven.

The point is to encourage, not oblige, because to embarrass any choice-asserting urban Kenyan writer for not writing in, say, Kikamba, is to humiliate her in exactly the same way as to laugh at the shrubber is to humiliate her, symbolically strip her naked and deny her 'Kenyanness'.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.