Good discourse, just like good science, ought to be grounded in two questions: What do we know? What are we going to learn?

This is how we should approach the chilling report by the Kenya Secondary Schools Heads Association (KSSHA) during their AGM in Mombasa last week; that 67 per cent of teachers and principals are dying from stress, heart attacks, high blood pressure, hypertension and other ailments triggered by stress.

Although it’s not clear how they arrived at their shocking statistics, one thing is clear: KSSHA knows why, as an organisation, it continues to lose employees. And we must give them credit for opening debate on such a crucial subject.

For starters, the World Health Organisation (WHO) is keen on workplace health promotion (WHP) because of its impact on the economic well-being of people, their organisations and nations.

It improves staff morale, creates a positive corporate image, reduces staff turnover, absenteeism, healthcare costs and risk of litigation, and improves morale and productivity.

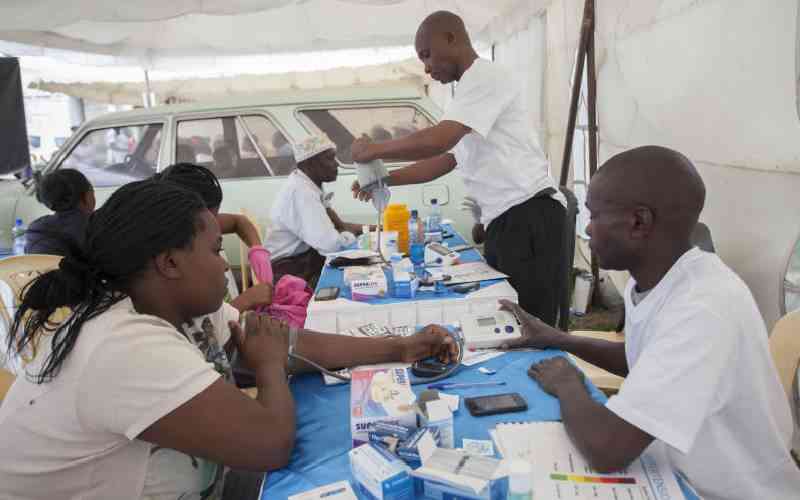

Recently, a health statistics report for East African countries showed that cardiovascular diseases and diabetes are the leading causes of death, followed by chronic respiratory diseases and cancer, for people below the age of 60.

Non-communicable diseases

The report further notes that Tanzania, Uganda and Kenya have higher numbers of people dying from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) than Burundi and Rwanda.

In 2006, WHO estimated 17 million people die every year due to cardiovascular diseases, in particular heart attacks and strokes.

This is why the statistic by the teaching fraternity are frightening. From an organisational point of view, such untimely deaths affect learning in many practical ways.

For instance, since it takes a good deal of time for the Teachers Service Commission (TSC) to replace teachers, a leadership and management void could distract learning as a lot of time is wasted on indecision and jostling for power.

But even more worrying is the cost and quality of education and its implications on the Government, as well as the performance of students, their families and entire communities.

Since there is a connection between NCDs, nutrition and exercise, the national and county governments are well placed to be enablers of diet and physical activity programmes in the workplace.

As a major employer, the national and county governments can and should lead by example, by promoting good nutrition and exercise for their employees. Through the Ministry of Health and other relevant Government departments, it can influence action at organisational and individual levels.

That is why Kenya needs a national strategic plan for NCDs that requires co-ordinated action from all concerned — multiple sectors within the national and county governments, communities, civil society, private sector, international partners, media, academic and research institutions.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Such a strategic plan would address the substantial economic cost related to a lack of exercise and poor nutrition — cited as some of the leading causes of NCDs — among the country’s workforce. It can, for instance, zero rate exercise equipment.

In August 2011, the first Kenya National Forum on NCDs was held in Naivasha, and among its recommendations was a call to the national government to “develop policy and legislative frameworks that create supportive environments for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases, including provision palliative care”.

This should be a good starting point for the parliamentary committee on health to make itself known.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.