By Charles Kanjama

It is four weeks before the 2012 elections, and the three-dozen presidential candidates have finally been whittled down to five serious contenders and a handful of marginal contestants. It has been a really open and interactive electoral process. Kenyans have quizzed the candidates on their economic, social and political views and manifestoes. Abuse of office claims has led some candidates to collapse spectacularly.

Several public debates have taken place, covered by the media, and sponsored by different stakeholders. There have also been interactive forums, similar to the town hall style engagements in America. These though have appeared rather scripted. For the last televised debate, the five serious contenders and their running mates will face nearly two hours of debate, dialogue and questions. All of Kenya is watching.

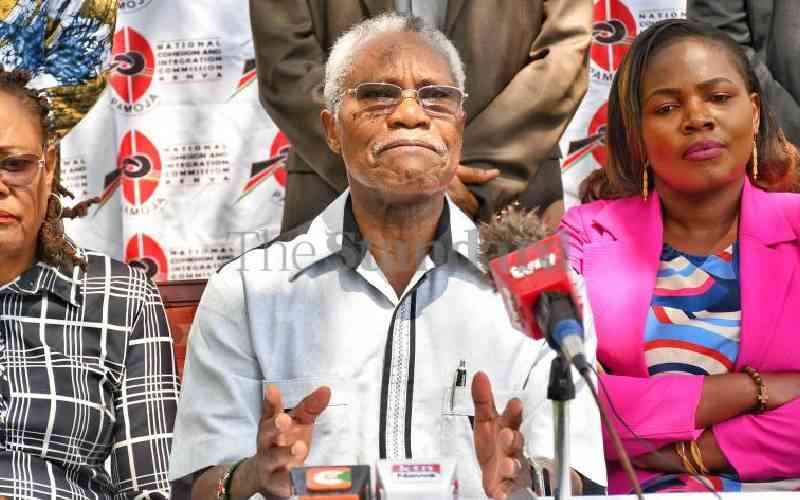

Happily, the NCIC-sponsored campaign dubbed Mulika Mkabila (‘Expose the tribalist’) has proved a success. Most media houses, led by the Media Council of Kenya, have signed up. Journalists are no longer reporting on ethnic dimensions of campaigns. Even political parties, forced by the weight of public opinion, are tagging along. Most talk of "our man", "our community" has subsided into the gutter.

Wouldn’t this be a great political scenario for next year? Wouldn’t it be great if media and political analysts will spend most of next year analysing the agenda and interactions of the candidates, but not their ethnicity vis-a-vis tribal arithmetic? In Kenya today, to be a realistic political analyst, one must be very conscious of ethnic, clan and other regional identities. I have always found this rather violating, the fact that you cannot critically analyse electoral scenarios without adopting ethnic arithmetic.

Yet the problem is not just that Kenyan media, whether national or regional, are focused on ethnicity as the primary factor of political organisation. The problem is that ethnicity is indeed the main factor in determining political alignments, both among political leaders, and among the ordinary Kenyan voters. So merely illegitimising ethnic political alliances do not dismantle them; it merely sends them below the radar. Mulika Mkabila on its own will not change our ethnic attitudes and political alignments.

There is a mysterious biblical parable about the man who was possessed by an evil spirit. The evil spirit left the man, and he kept his soul swept up and clean. The spirit travelled all over the place, and then found seven spirits worse than itself. They came back and possessed the man, so that his last state became worse than his first. This parable has always struck me due to its unlikely outcome and its subtle message.

In short, it is not enough to expel one ill unless we fill the space left behind with a good replacement. Nature abhors a vacuum. And society cannot stand in the absence of networks. So the big question is not whether we can eradicate ethnicity as the basis for social and political organisation. Because ethnicity in itself is neutral, while ethnic diversity is positive and tribal prejudice is negative.

The big question is, ‘what do we replace ethnic politics with?’ If we replace ethnicity with class, race, gender or other forms of identity politics, we will have merely substituted one ill for another. Not even ideological polarity under a foundation of secularism is the answer for Kenya’s future politics. Politics need not be an oscillation between liberal and conservative politics, where liberalism is understood as freedom from the tyranny of tradition, and conservatism as freedom from the tyranny of the brave.

Yet true politics is always an interaction between competing creeds and personalities.

So let us craft an issue-based politics that can rescue us from the identity politics of ethnicity with its twin ills of prejudice and division.

—The author is an Advocate of the High Court of Kenya

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.